Paracas Art and Architecture Object and Context in South Coastal Peru

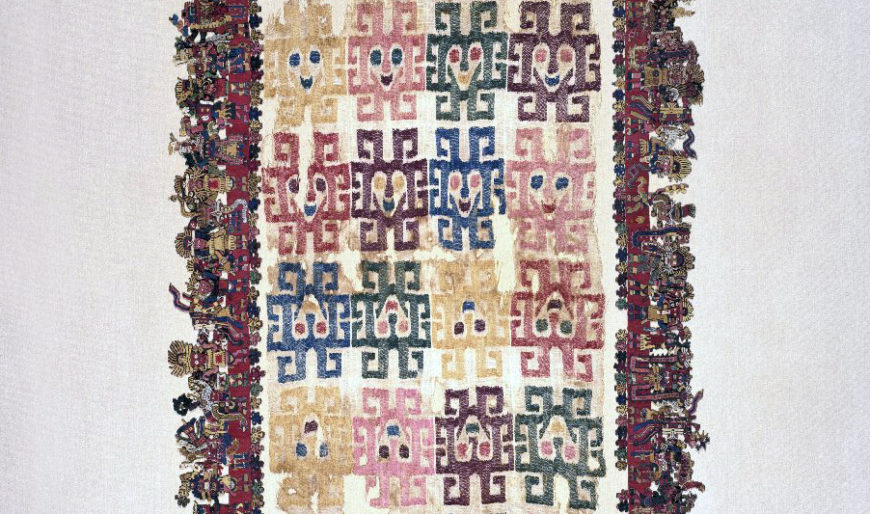

Nasca, Mantle ("The Paracas Textile"), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 10 24–i/2 inches / 148 x 62.2 cm, found s coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Mummy bundles

1 of the nearly extraordinary masterpieces of the pre-Columbian Americas is a near two,000-year-erstwhile textile from the South Coast of Peru, which has been in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art since 1938.

Despite the textile's small size (information technology measures about two by 5 feet), it contains a vast amount of data well-nigh the people who lived in ancient Peru; and despite its great age and effeminateness, its colors are brilliant, and tiny details amazingly intact. This is due to the arid surround of southern Peru along the Pacific shore, where information technology is so dry that organic textile cached in the sand remains well preserved for hundreds or fifty-fifty thousands of years.

Paracas National Reserve, Peru (photo: Edubucher, CC Past two.0)

The Paracas peninsula, Peru (underlying map © Google)

In the aboriginal cemeteries on the Paracas Peninsula, the dead were wrapped in layers of cloth and clothing into "mummy bundles." The largest and richest mummy bundles contained hundreds of brightly embroidered textiles, feathered costumes, and fine jewelry, interspersed with nutrient offerings, such as beans. Early reports claimed that this fabric came from the Paracas peninsula, and then it was called "THE Paracas material," to marker its excellence and uniqueness. Currently, scholars have revised this provenance, and at present attribute the cloth to the related, merely slightly later Nasca culture.

Thread past thread

Recently, the Brooklyn Museum has posted high quality, close-up views of this masterpiece online, allowing viewers to scrutinize the fabric, thread by thread. Such a detailed inspection has not been possible since the slice was first made. With simple tools, the early cultures of the Andean region of South America produced textiles of astonishing virtuosity. Some extremely fine pieces, like this one, are besides frail to have served any utilitarian purpose, and then are considered formalism.

Detail of edge figure 61, Nasca, Curtain ("The Paracas Textile"), 100–300 C.Due east., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–i/four x 24–1/2″ / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Republic of peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Like some other very fine cloths, the Brooklyn textile is finished so carefully on both sides that it is almost impossible to distinguish which is the correct side. Although the central cloth and its framing dimensional edge are created past different techniques, both display perfect reversibility—except for three border figures. These three—instead of being duplicated on the dorsum (as if flipped in mirror prototype), similar all the others—announced in back view on one side of the cloth, thereby designating a "front end" and "back" to the textile.

Center detail, Nasca, Mantle ("The Paracas Textile"), 100–300 C.Eastward., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2 inches / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south declension, Paracas, Republic of peru (Brooklyn Museum)

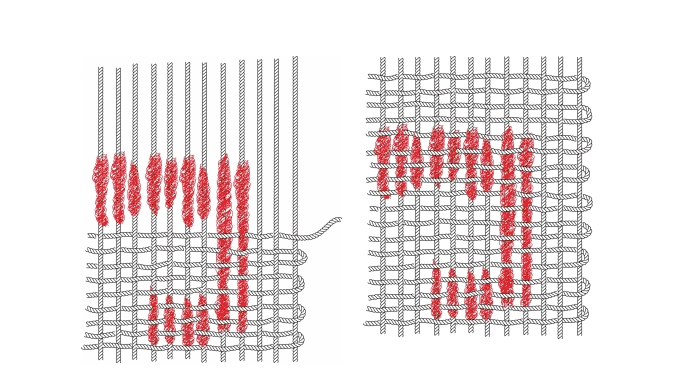

Warp wrapping (diagram by Lois Martin)

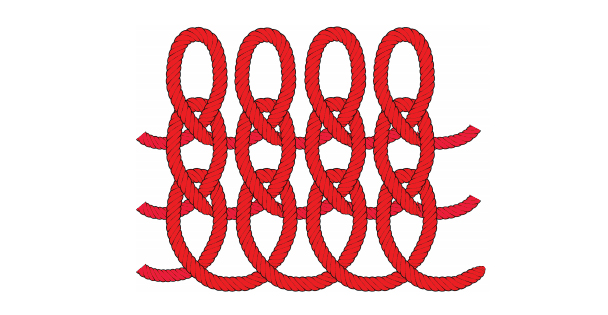

The central cloth's design of 32 geometric faces is created by "warp-wrapping," a technique in which colored fleece is wound around sections of cotton fiber warp threads earlier weaving. Because the central textile and the edge take different color palettes, they may take been created at different times. The triple-layer edge has colorful outer veneers of wool "crossed-looping" that envelop inner cotton cores of looping or weaving.

Crossed looping (diagram by Lois Martin)

"Crossed-looping" resembles knitting (but is accomplished with a single needle); in areas where the threads are broken, information technology is possible to glimpse the underlying cotton wool substrates. While the cotton is off-white, the wool is dyed in precious stone-brilliant tones.

Alpaca herd, Ausangate, Peru (photograph: Marturius, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The combination of materials suggests extensive trading relationships: for while cotton was grown in coastal valleys, wool came from camelids (such equally the llama, alpaca, and vicuña) that live at high altitudes in the Andes mountains.

The llama is laden with a bounty of vegetables. Since pre-Columbian people had no wheeled vehicles for transport, llama caravans carried goods between regions. Border figure 26, Nazca, Pall ("The Paracas Cloth"), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 ten 24–1/2 inches / 148 10 62.2 cm, plant south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Monstrous hybrids

On the border, a parade of ninety figures is linked together on their lower bodies, which are worked 2-dimensionally confronting a red background.

Detail of border figures (composite photo), Nasca, Curtain ("The Paracas Material"), 100–300 C.E., cotton fiber, camelid cobweb, 58–i/4 10 24–ane/two inches / 148 ten 62.2 cm, found southward declension, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Each figure's upper body and head is synthetic as a separate unit, and attached to the woven strip. The upper bodies are worked in bas-relief, with some parts projecting outwards from the airplane of the fabric. Tiny components (similar leaves and feathers) were worked as separate pieces then attached, giving a wonderful iii-dimensionality and liveliness to the figures, especially because they mingle and overlap.

Nasca, Drape ("The Paracas Textile"), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–i/4 x 24–1/2 inches / 148 ten 62.2 cm, found southward coast, Paracas, Republic of peru (Brooklyn Museum)

The parade is arranged in four, single-file, L-shaped lines that proceed around each corner of the material. A wide variety of types appear, including human, animal, and monstrous hybrids. Some figures are unique, others are twins, triplets, or even sextuplets; a few are in related groups.

Most of the animals and plants that appear tin be tied to species still found on the South Declension, and many human figures clothing or carry items that directly relate to the archaeological tape.

Nasca mouthmask, 300–700 C.E., aureate with cinnabar, Republic of peru (de Immature Museum, San Francisco)

Their jewelry, for instance, corresponds to specimens formed from thin sheets of gleaming gold. These include: "brow ornaments" (shaped similar a bird with outstretched wings); "hair spangles" (disk or star shapes that dangle from the wingtips of the forehead ornament); slender, plumage-shaped headdress "plumes;" and "mouthmasks." Mouthmasks hung from the olfactory organ septum, and had flaring extensions, like cat whiskers.

Particular with face up decoration, border figure 63, Nasca, Mantle ("The Paracas Textile"), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–i/four ten 24–1/ii″ / 148 10 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Garments

The border figures' wear besides matches examples plant archaeologically, and some carry minuscule designs that faithfully correspond embroidered decorations constitute on life-sized garments. Some article of clothing wrap-around dresses of a style worn past women in ancient times; others vesture 2-part outfits, associated with men (below). The largest and virtually beautifully decorated garments were mantles that draped over the shoulders, and savage to the human knee. By examining stitches on bodily mantles, archaeologists have determined that teams of artists worked on them, sitting side-by-side.

One of three figures with a front end and back, painted or tattooed skin, wears a bristling mouthmask, and a headdress with flower-like plumes. He carries a striped staff topped with a winged creature, and wears a tunic and loincloth. Over his shoulder hangs a boldly-patterned pall ending in a feline. Detail of border effigy xvi, Nasca, Curtain ("The Paracas Fabric"), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid cobweb, 58–1/4 10 24–ane/ii″ / 148 10 62.2 cm, found south declension, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Other edge details, rather than realistic, seem to be fantastic or mythological. The severed heads (sometimes called "trophy heads") brandished by some figures, for example, sometimes sprout flourishing plants—as if to suggest themes of sacrifice and fertility. And snake-like streamers that flow from some figures do not correspond to any known object, and may indicate supernatural qualities.

Pampas cat and tree, border figure 3, Nasca, Mantle ("The Paracas Cloth"), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid cobweb, 58–1/4 x 24–ane/2″ / 148 x 62.two cm, found southward coast, Paracas, Republic of peru (Brooklyn Museum)

When they depicted clothing, Paracas and Nazca artists often added a face, or an brute body to the loose ends of fabric hanging behind a wearer. This artistic convention seems to suggest the lively movements of textile fluttering behind a wearer, and hints that these ancient people considered textile a precious carrier of vitality: an estimation that seems warranted considering this vibrant textile gives us such an evocative and blithe glimpse into their globe.

Backstory

The Paracas Textile is just ane of hundreds of similar textiles that originate from multiple burying sites on the Paracas peninsula. These burials were first identified and excavated by the renowned Peruvian archeologist Julio Tello in the 1920s. For political reasons, Tello was forced to abandon the site in 1930, and, without a team of archaeologists to oversee the area, a menstruum of intense looting followed. It is now believed that a cracking number of the Paracas textiles in international museum collections were acquired as a event of this looting, which occurred most heavily between 1931 and 1933.

A large group of these illegally acquired textiles is held by the Gothenburg Drove in the Museum of Earth Culture in Gothenburg, Sweden. The objects were smuggled out of Peru by the Swedish consul in the early 1930s, and donated to the urban center of Gothenburg. The museum and urban center fully admit the objects' illicit provenance, and have been working with the Peruvian government on a programme for their systematic return. As stated on the museum website,

Large quantities of Paracas textiles were illegally exported to museums and individual collections all over the earth between 1931 and 1933. Most a hundred of these were taken to Sweden and donated to the Ethnographic Department of Gothenburg Museum. Today, issues associated with looted artifacts and illicit merchandise in antiques are better acknowledged and being addressed.

Though Peru began lobbying for repatriation in 2009, Gothenburg has been somewhat slow to reply to the requests, partly due to the fragile condition of the textiles. According to the museum website, even the transport of these objects between the museum'south archives and their exhibition space in Sweden—a altitude of just a few kilometers—has resulted in their deterioration. Despite these concerns, a program has been put in place to systematically return some of the textiles to Peru. The beginning four were delivered in 2014, and another 79 in 2017. Farther works are ready to be returned past 2021. The repatriated textiles are now in the possession of Republic of peru's General Directorate of Museums of the Ministry of Culture.

The case of the Gothenburg Paracas textiles highlights the need not only for governmental and institutional agreements regarding the restitution of illegally caused objects, but too for oversight apropos the connected stewardship and preservation of these fragile artworks.

Backstory past Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

Additional resources:

This textile at the Brooklyn Museum

The Gothenburg Collection of Paracas textiles

Article on the annexation of Paracas textiles on Trafficking Culture

"Republic of peru recovers 79 pre-Hispanic textiles illegally kept in Sweden," The Local, December 15, 2017

"Peru recovers Paracas textiles," Diario UNO, December xv, 2017

"Sweden Returns Ancient Andean Textiles to Peru," The New York Times, June 5, 2014

Frame, Mary. 2003–4. "What the Women Were Wearing: A Eolith of Early Nasca Dresses and Shawls from Cahuachi, Peru." Textile Museum Journal, 42/43:13–53.

Paul, Anne. 1990. "Paracas ritual attire: symbols of dominance in ancient Republic of peru,"Civilization of the American Indian series. Norman: Academy of Oklahoma Press.

Paul, Anne. 1991. Paracas art & compages : object and context in S Coastal Peru, 1st ed. Iowa Urban center: Academy of Iowa Press.

Silverman, Helaine. 2002. "Differentiating Paracas Necropolis and Early Nasca Textiles,"Andean archaeology II: Art, Mural, and Order, edited by Due west. H. Isbell and H. Silverman. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 71–105.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

More Smarthistory images…

Source: https://smarthistory.org/the-paracas-textile/

0 Response to "Paracas Art and Architecture Object and Context in South Coastal Peru"

إرسال تعليق